The Tale of Two Champions: the Porsche 956 and 962

- 4 Mar 2019

- Racing

By Bill Oursler

By Bill Oursler

What follows is the story of a half love-hate American motorsport relationship that began at the start of the 1970s, and lasted nearly decade and a half. The marriage of convenience produced two prototypes and went on to shape sports car racing on the western side of the Atlantic and eventually around the world.

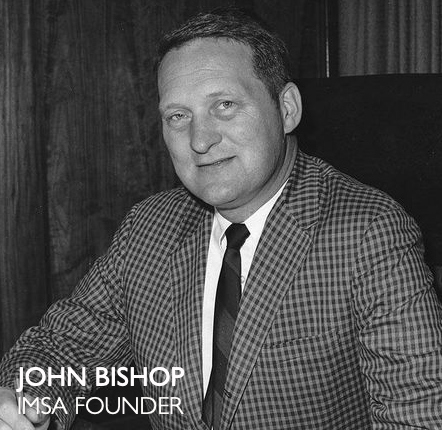

On one side this relationship was John Bishop, who, with the financial help of NASCAR’s Bill France, Sr., founded of the International Motorsports Association in 1969. On the other side was Porsche, the German manufacturer used IMSA sanctioned events to dominate sports car racing in North America from the 1970s through to the first part of the 1980s. While the union proved beneficial for both, it did so in a nearly constant state of turmoil born out of their conflicting goals. For Bishop a partnership with Porsche helped increase crowd pleasing fields anchored by the drawing power of German cars. Porsche used the on track victories to boost street- car sales and building a name for itself as a leading sports car manufacturer in the process.

On one side this relationship was John Bishop, who, with the financial help of NASCAR’s Bill France, Sr., founded of the International Motorsports Association in 1969. On the other side was Porsche, the German manufacturer used IMSA sanctioned events to dominate sports car racing in North America from the 1970s through to the first part of the 1980s. While the union proved beneficial for both, it did so in a nearly constant state of turmoil born out of their conflicting goals. For Bishop a partnership with Porsche helped increase crowd pleasing fields anchored by the drawing power of German cars. Porsche used the on track victories to boost street- car sales and building a name for itself as a leading sports car manufacturer in the process.

The conflict arose from Porsche’s desire to dominate the IMSA scene. Bishop fought equally hard to prevent just that. The venerable promoter strongly believed on domination by one marque would drive away competitors and fans alike.

Things came to a head as the 80’s dawned and were shaped not by events in America, but in Europe. After struggling to keep the prototype category alive, the sports world wide governing body, the Federation International de L’Automobile (FIA), announced its Group C prototype regulations that would start in 1982.

The Group C rules were fairly open to design but unlike previous prototype iterations were not dictated by engine displacement but by fuel economy. Strict limits were placed on the amount of fuel the cars would be given to complete the race distance. Bishop felt, that approach was not one that would be attractive to American spectators, who were, accustomed to paying their money to see cars being pushed to their limits, rather than parading around to conserve enough fuel to see the checkered flag.

Bishop, always known for not being afraid to go his own way, launched his own prototype class for IMSA called GTP (Grand Touring Prototype). The new GTP cars would race to a power-to-weight formula, rather than a fuel economy based set of regulations. Although Bishop hoped chassis makers would compete in both the FIA and IMSA series, there was buried within Bishop’s scriptures one small, but significant, difference in chassis regulations that would change the future of the IMSA-Porsche relationship. The clause in question said a driver’s feet could not be positioned ahead of the front axle line, as was the case with the monocoque chassis of Zuffenhausen’s Group C 956 prototype.

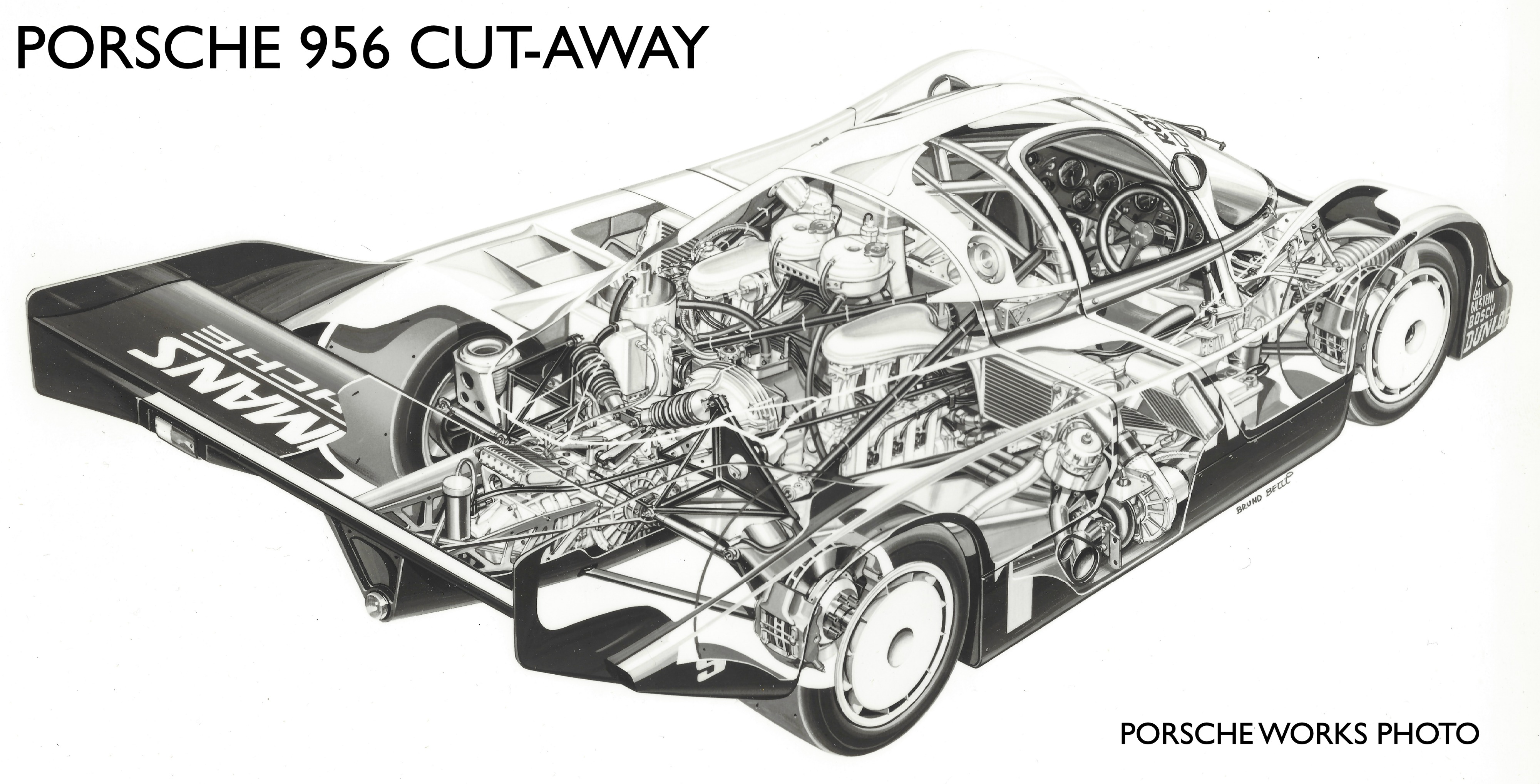

At the time the 956 was designed like every Porsche prototype since 1967 with the driver’s feet positioned head of the front axel. This design philosophy dates back to when Porsche began dominating the, then, very important hill-climb arena. The design standard was born out of Porsche’s desire to build the best machines possible for winning the hill-climb events by reducing weight of the cars as much as possible to get the utmost power to weight ratio.

At the time the 956 was designed like every Porsche prototype since 1967 with the driver’s feet positioned head of the front axel. This design philosophy dates back to when Porsche began dominating the, then, very important hill-climb arena. The design standard was born out of Porsche’s desire to build the best machines possible for winning the hill-climb events by reducing weight of the cars as much as possible to get the utmost power to weight ratio.

Remarkably, Porsche was able to get the weight of its championship winning hillclimb spyders down to just over one thousand pounds. However, as the cars grew ever lighter the weight differential became increasingly unbalanced with the increasing majority of the weight being carried by the rear axel. The factory’s solution to this problem was to move the car’s engine and gearbox forward in the chassis; so far so that the driver’s feet wound up ahead of the front axle line. The approach worked so well, it was then incorporated in every subsequent sports racing Porsche prototype up through the 956

When 956 concept came to fruition, Porsche had only ever raced production-based machines in IMSA, 911s and it’s derivatives the 934 and 935 were the Porsches that won races in IMSA. Prototype Porsches were prevalent only in international events run to FIA rules that allowed the feet forward design used by Zuffenhausen. That Porsche stopped racing prototypes stateside was a consequence of Bishop’s using the position of the driver’s feet as an excuse to bar a re-engined version of Zuffenhausen’s Group C prototype chassis from dominating his championship on the grounds of driver safety.

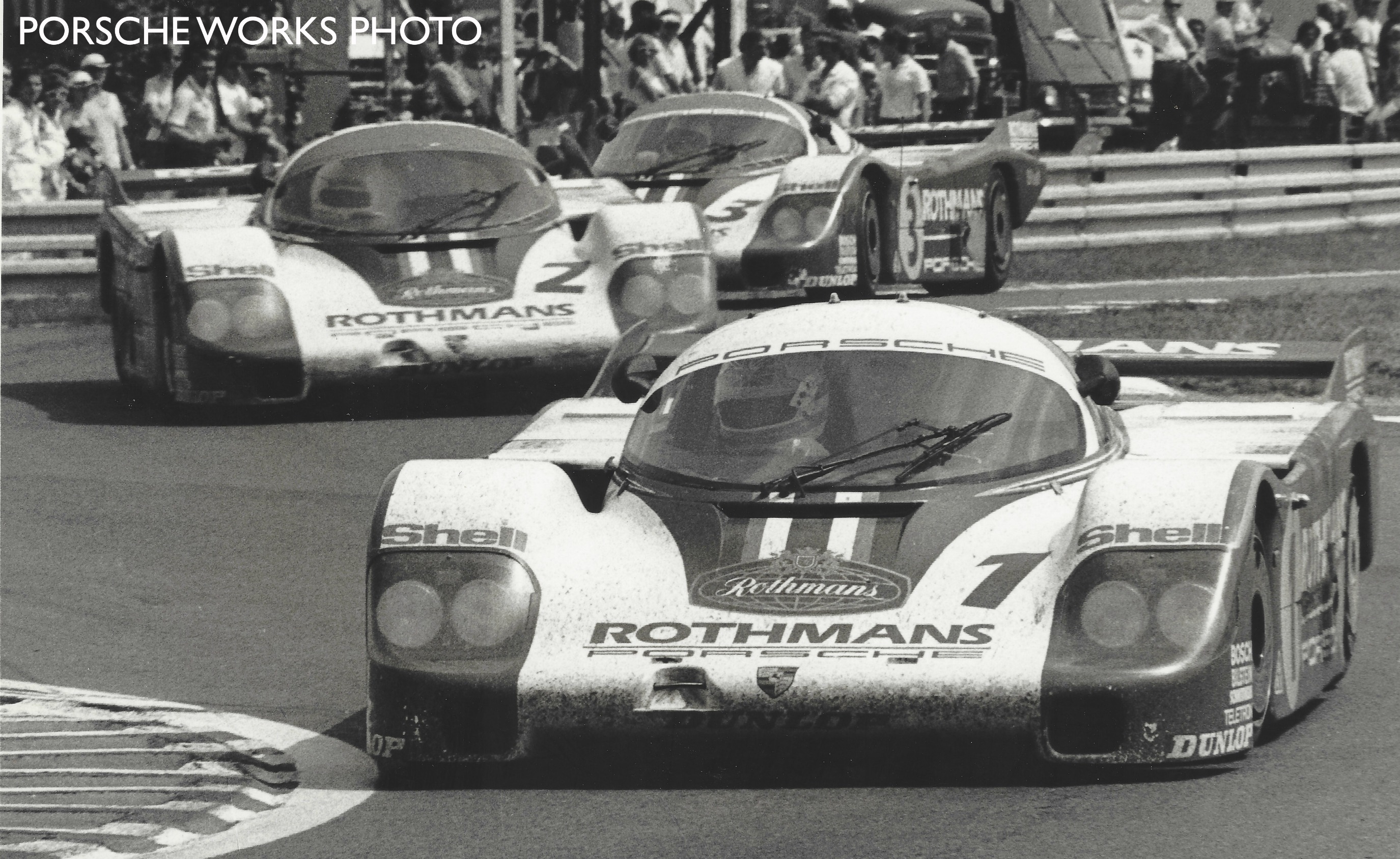

In truth, while clearly locating the feet so far forward was less safe than had they been placed behind the front axle, there had been few, if any, serious injuries from doing so. In the short  term, at least, it seemed like a good ploy, especially in light of the 956’s overwhelming initial success, a sweep of the podium at the debut Le Mans for the 956 in 1982. In fact, 956’s would claim no less than four straight Le Mans triumphs between 1982 and 1985. Even though the 956 had been “locked out“ of GTP category and was winning lots of races in Europe, both Porsche and its customers kept a close watch on Bishop’s series

term, at least, it seemed like a good ploy, especially in light of the 956’s overwhelming initial success, a sweep of the podium at the debut Le Mans for the 956 in 1982. In fact, 956’s would claim no less than four straight Le Mans triumphs between 1982 and 1985. Even though the 956 had been “locked out“ of GTP category and was winning lots of races in Europe, both Porsche and its customers kept a close watch on Bishop’s series

That American based US series still featured Porsche still enjoying great success in America. John Paul Jr. dominated the IMSA series in the venerable JLP Porsche 935-3 and 4 models. Just before the start of the following season, Porsche made clear the potential of a return to IMSA, announcing that it would investigate the possibility of building a new car to meet the sanctioning body’s regulations.

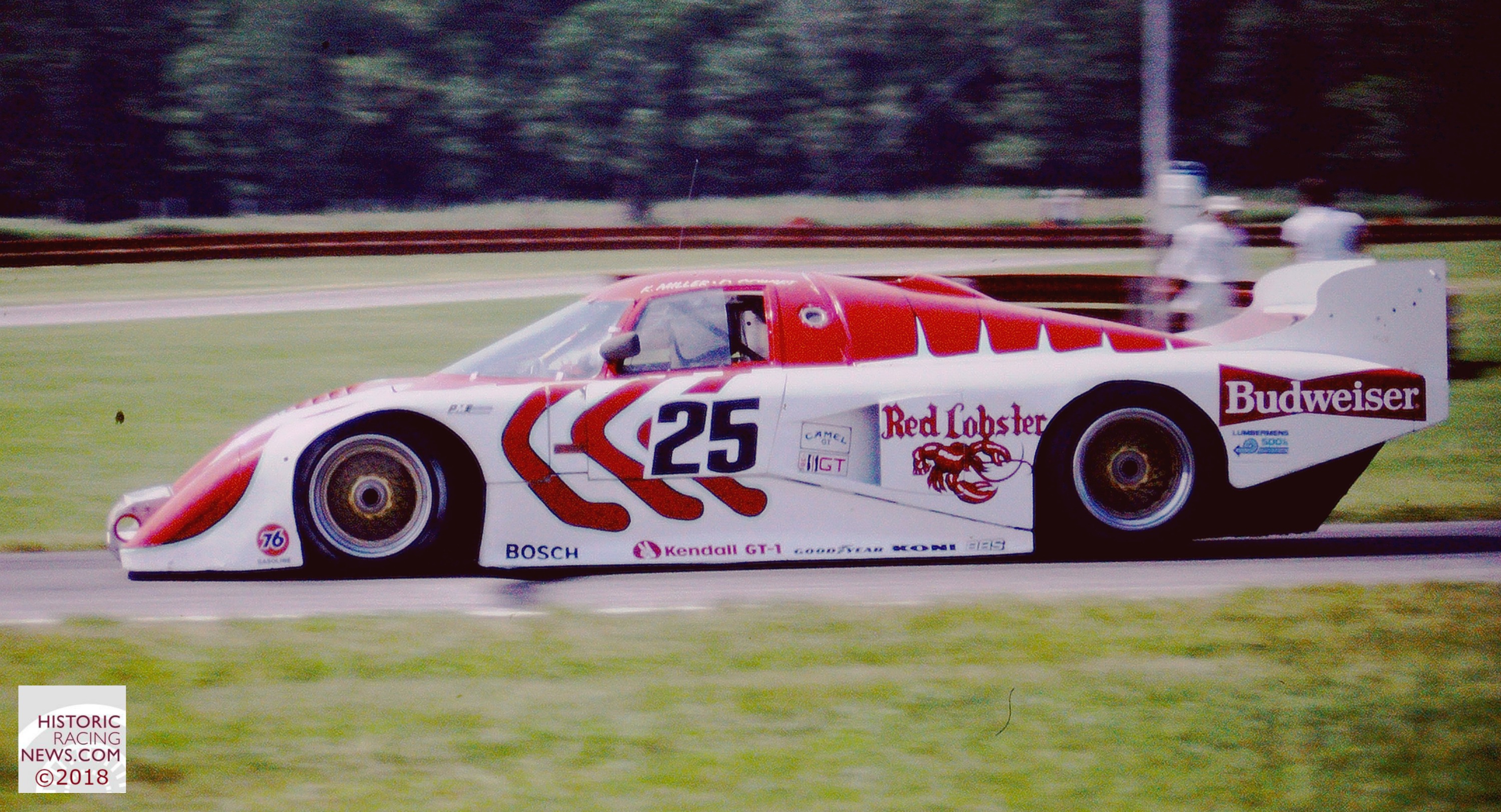

Another hint of Zuffenhausen’s plans came in a slightly more subtle form with the revelation that Dave Cowart and Kenner Miller would enter a Porsche powered March 82G in IMSA with Red Lobster sponsorship along with Porsche stalwart, and future head of Porsche Motorsport North America, Al Holbert fielding his own Porsche-March 83G. Holbert shared his March with Mid Ohio track owner, Jim Truman. That duo went on to claim the 1983 IMSA Camel GT Championship. While Holbert and Truman were barnstorming the American racetracks Jürgen Barth, then the head of Porsche’s customer racing programs, met quietly with Bishop at IMSA’s Bridgeport Connecticut headquarters in July of 1983.

During that session Barth offered two solutions to the stalemate. Porsche would strengthen and reinforce the foot box, or take the drastic step of building a completely new prototype to go racing in the USA. You can bet what Bishop chose and shortly after that meeting it was confirmed that Zuffenhausen would build a brand new IMSA legal version of its Le Mans winning 956. Thus was born the 962. No one would know it then, but this prototype would come to dramatically impact not just IMSA’s future, and the sports car world itself.

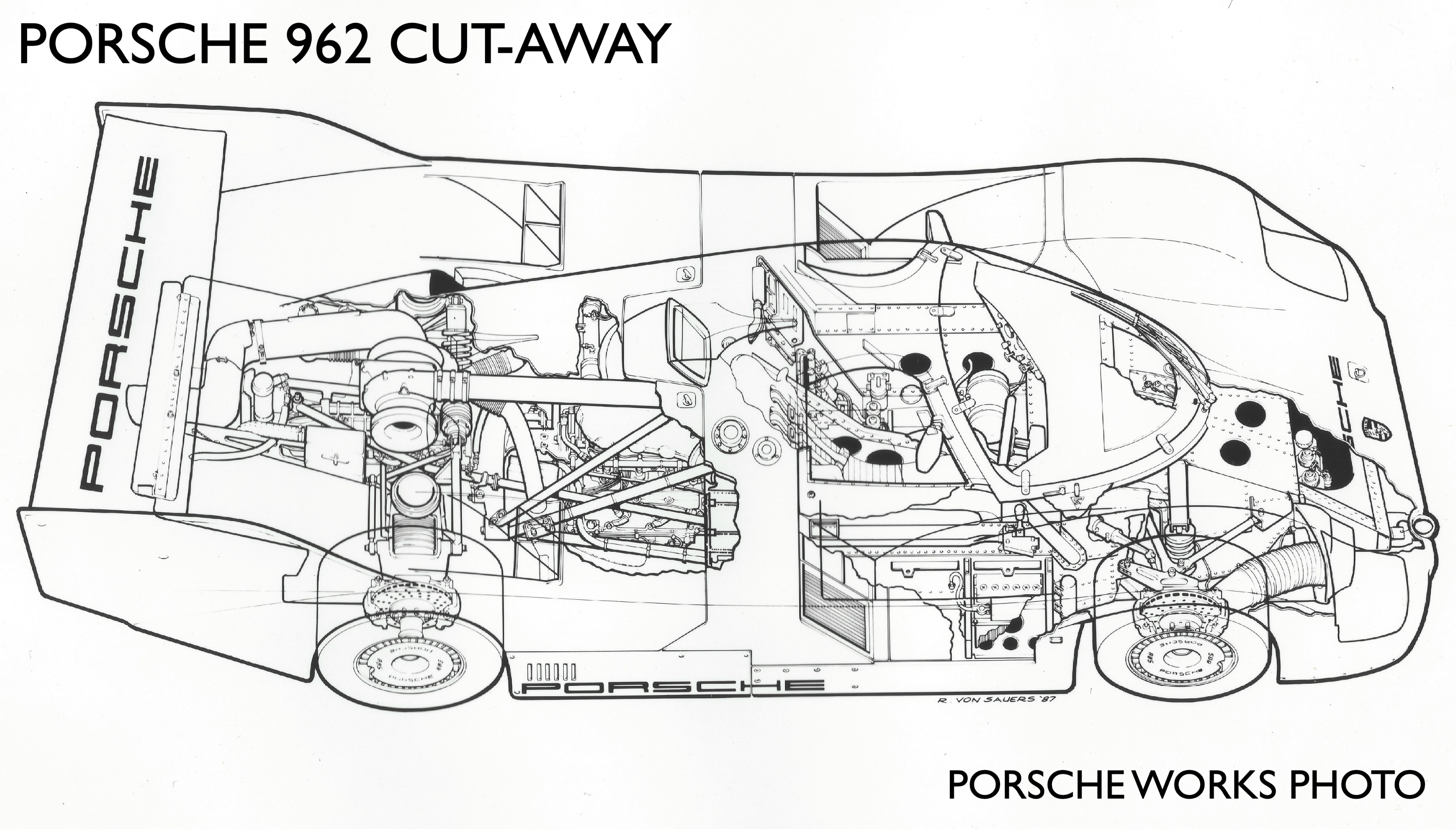

The man put in charge of developing the 962 was, Norbert Singer. Singer was the man responsible for developing the factory’s dominating 911 Carrera RSRs, and the awesome turbocharged 935s. He had also led the engineering team that crewed the original 956. Given that the major difference between the two prototypes was the need to extend the 962’s front wheelbase to accommodate the repositioning of the driver’s feet behind the front axle line, conventional wisdom said that should have been a relatively easy task. But, it wasn’t. The reason why involved the car’s aerodynamics.

The man put in charge of developing the 962 was, Norbert Singer. Singer was the man responsible for developing the factory’s dominating 911 Carrera RSRs, and the awesome turbocharged 935s. He had also led the engineering team that crewed the original 956. Given that the major difference between the two prototypes was the need to extend the 962’s front wheelbase to accommodate the repositioning of the driver’s feet behind the front axle line, conventional wisdom said that should have been a relatively easy task. But, it wasn’t. The reason why involved the car’s aerodynamics.

The way Singer described it, what complicated the issue centered on the rules governing the vehicle’s front and rear body overhangs. To make the car legal in both IMSA and FIA sanctioned events in Europe engineers had to walk a tightrope. Said Singer: ”Because the FIA had placed strict dimensional limitations on the length of the overhangs, it was difficult for us to reconfigure them so they again worked properly. Fortunately, in the end, however, we were able to get it right.”

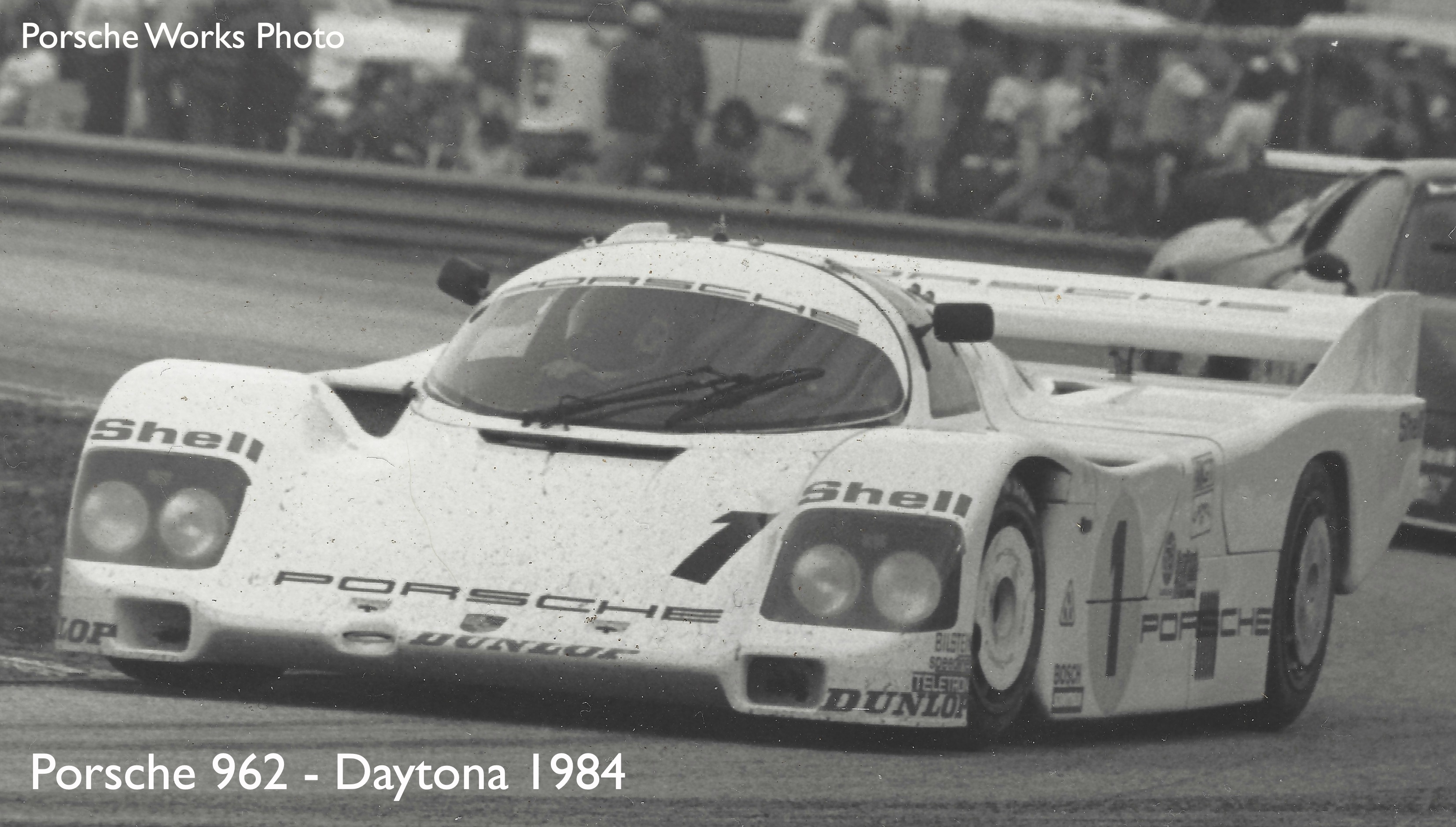

American privateer Bruce Leven had been scheduled to receive the first of the 962s, but the factory chose to debut the car itself, entering it at the ’84 Daytona 24 Hours with drivers Mario and Michael Andretti.

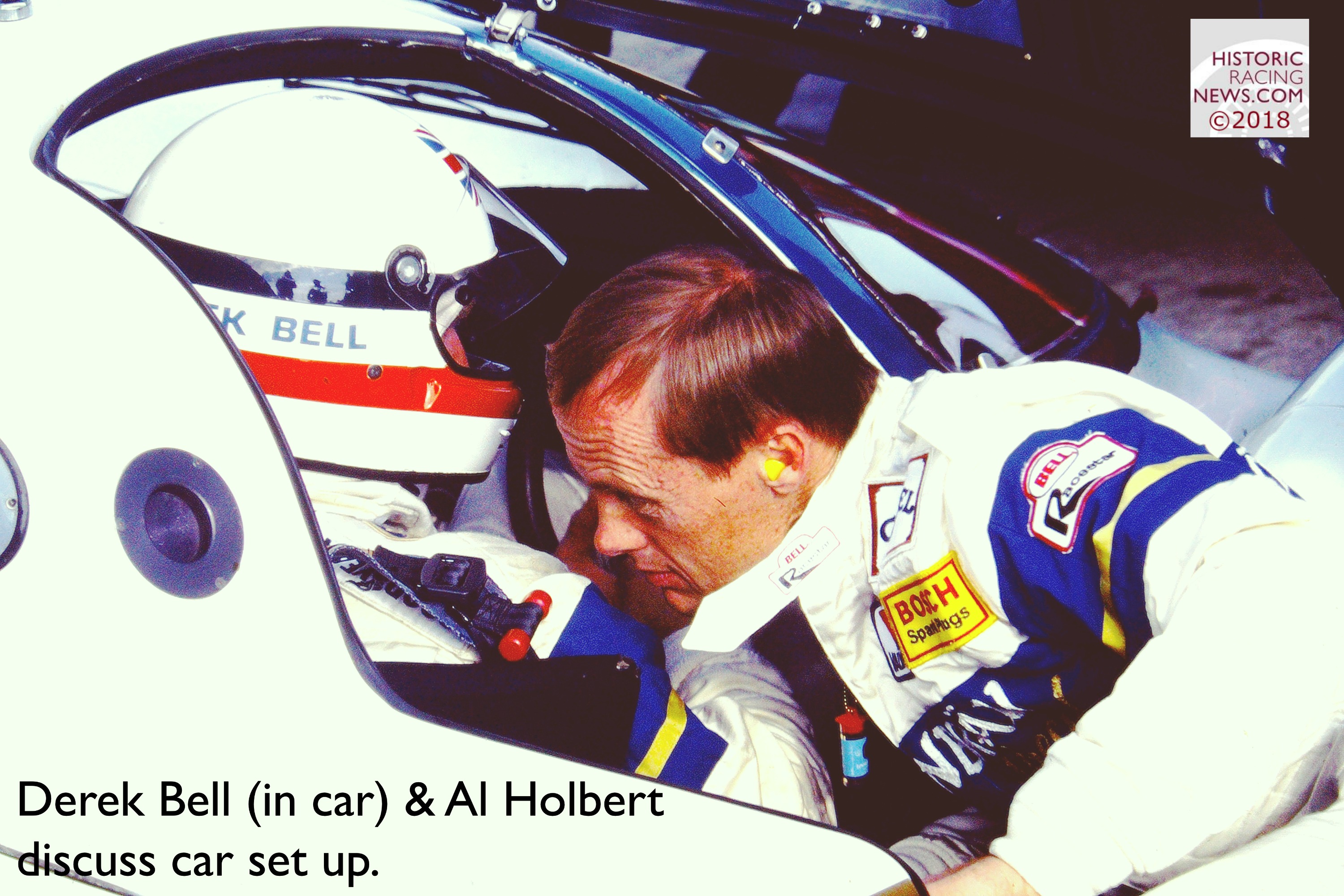

The 962 showed promising performance before mechanical problems led to its early retirement. Holbert then took delivery of his 962 in late April and finished second at its debut event, the classic 6-hours of Riverside. As for Leven, his 962 arrived in May in time for the spring run at Laguna Seca, driver Derek Bell finishing 8th. Bob Akin took delivery of his 962 in time for a debut run on the roval at Charlotte but mechanical issues ended his run early.As had been the case with the factory Daytona entry, all were forced to use the air-cooled version of the 935’s boosted six, rather than the water-cooled head variant employed by the 956. Those engine specifications were another concession to Bishop, who saw it as a way of keeping the new entry from totally dominating its opposition.

The 962 showed promising performance before mechanical problems led to its early retirement. Holbert then took delivery of his 962 in late April and finished second at its debut event, the classic 6-hours of Riverside. As for Leven, his 962 arrived in May in time for the spring run at Laguna Seca, driver Derek Bell finishing 8th. Bob Akin took delivery of his 962 in time for a debut run on the roval at Charlotte but mechanical issues ended his run early.As had been the case with the factory Daytona entry, all were forced to use the air-cooled version of the 935’s boosted six, rather than the water-cooled head variant employed by the 956. Those engine specifications were another concession to Bishop, who saw it as a way of keeping the new entry from totally dominating its opposition.

In that regard, Bishop's fears of the 962 being dominate right out of the box were premature. It wasn’t until the classic Lumberman’s 500 at Mid-Ohio, 8 races after its Daytona debut, that the 962 was able to claim the top spot on the podium in the hands of Holbert and his driving partner, Derek Bell.

By time Holbert and Bell claimed that first win, he and his two 962 counterpart owners, were already beginning to modifying their cars; trading in the original Le Mans style long tails for the short ones used by the European 956s in the normally slower sprint race rounds. Those changes brought steady improvement. The final tally from the inaugural season for the 962 showed 5 victories (all by Holbert) and 8 podium finishes for the three original 962 runners and Preston Henn who took delivery of his 962 in time for the season finale at Daytona. Those performances included two 1-2 finishes for Holbert and Leven at Watkins Glen and Road America.

By time Holbert and Bell claimed that first win, he and his two 962 counterpart owners, were already beginning to modifying their cars; trading in the original Le Mans style long tails for the short ones used by the European 956s in the normally slower sprint race rounds. Those changes brought steady improvement. The final tally from the inaugural season for the 962 showed 5 victories (all by Holbert) and 8 podium finishes for the three original 962 runners and Preston Henn who took delivery of his 962 in time for the season finale at Daytona. Those performances included two 1-2 finishes for Holbert and Leven at Watkins Glen and Road America.

On the heals of that strong American performance, international racing politics gave the 962 a big boost and set it up as the car to dominate on the world stage. The FIA announced it would follow IMSA’s lead on safety grounds and bar the 956 from competition because of foot box positioning. What had been an American only exercise, now had achieved a global status; and all because one man stuck to his principals and used the positioning of a driver’s within the structure of the car for safety as well as to keep it from dominating his motorsport domain.

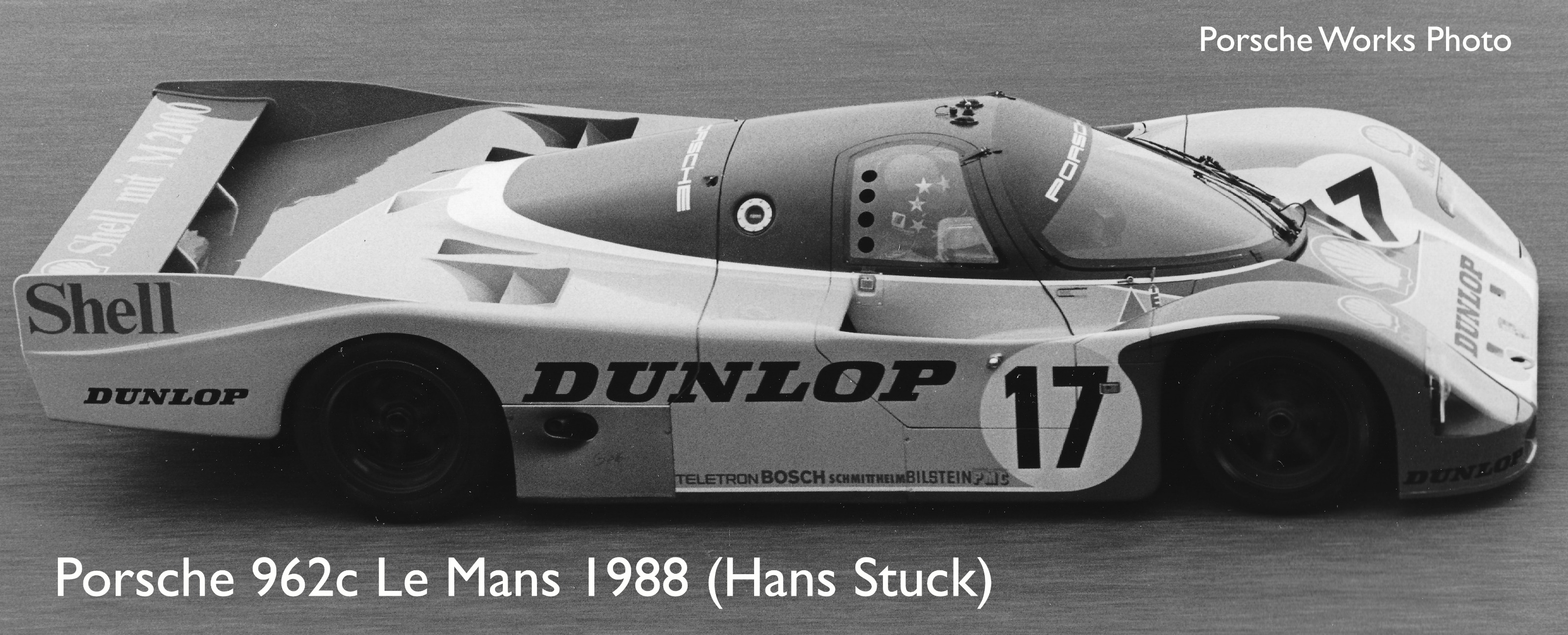

Even so, while the factory quickly replaced the 956 with the 962C, Porsche gave the “C” designation to the European versions because the were able to retain their water cooled powerplants while the IMSA entries kept their air cooled ones until 1988, when IMSA allowed the European versions in.

Even so, while the factory quickly replaced the 956 with the 962C, Porsche gave the “C” designation to the European versions because the were able to retain their water cooled powerplants while the IMSA entries kept their air cooled ones until 1988, when IMSA allowed the European versions in.

Despite the handicap of their air-cooled engines, the IMSA 962 teams quickly found their “groove”, and enjoyed three years of domination. 962 entries won all but one of the 17 races in 1985, 12 of 18 races in 1986, 13 of 16 events in 1987. From the cars debut in at Daytona in 1984 the 962 won 46 of the 68 IMSA races entered through the end of 1987. A stunning record that would not be duplicated until Audi and it’s dominate R8 run in the American Le Mans Series earlier this century.

The 962’s dominance came to an end in 1988 with tight restrictions placed on the Porsche coming at the same time Nissan had gotten things right with the GTP ZX-Turbo GTP. The Porsches staid competitive but more restrictions as well as advances from Nissan and later Toyota eventually the 962’s became uncompetitive and eventually passed from the scene.

The 962’s dominance came to an end in 1988 with tight restrictions placed on the Porsche coming at the same time Nissan had gotten things right with the GTP ZX-Turbo GTP. The Porsches staid competitive but more restrictions as well as advances from Nissan and later Toyota eventually the 962’s became uncompetitive and eventually passed from the scene.

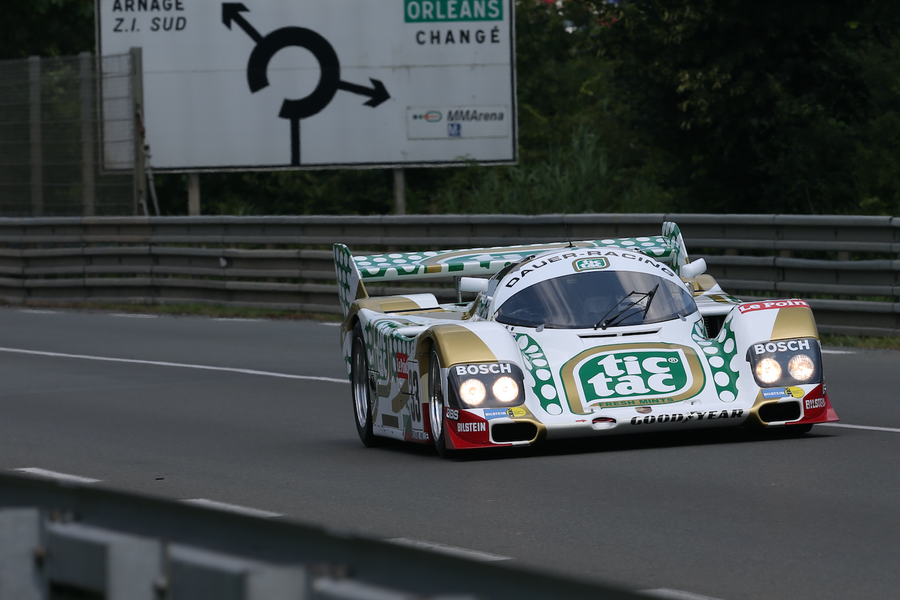

As for Europe, the 962Cs and the older 956s’were able to stay on form winning the famed 24-Hours of Le Mans a combined 6 straight times and 962Cs remained podium finishers until 1990. That was when Tom Walkinshaw’s factory supported Jaguar team and the factory Mercedes Silver Arrows C9s put their stamp on the FIA’s World Sports Car Championship. The 962 enjoyed a last hurrah with an outright win at the Sarthe in 1994 with a 962 that was not classified as a prototype, but rather as a GT car.

Looking back, Singer and company had produced two cars, the 956 and the 962/962C that were not only legendary, but, more importantly, they helped to save the sports racing prototypes from history’s dust bin. Prototype racing had all but died after the end of the Group 5 Ferraris and Porsches in the early 70s. Then these two Porsches, because of multiple wins on the sports car world’s biggest stage, the 24-Hours of Le Mans and 6 years of success in the world’s biggest performance car market the United States, made prototype racing relevant again. A relevance that has carried over all the way to our modern World Endurance Championship and American based WeatherTech Sports Car Championship we enjoy today. So now you know the behind the scenes story and the men behind it, of how sports prototype racing was shaped by a free thinking team of engineers from Zuffenhausen, a legendary stubborn American promoter, and two cars that will be remembered long after we’re gone.

Header picture: DailySportscar.com/David Lord