On This Day: When the World Held its Breath

- 23 Apr 2019

- On This Day

By Paul Tarsey

By Paul Tarsey

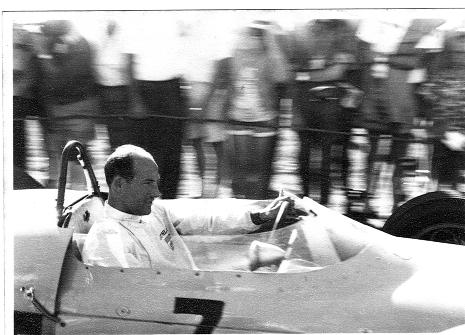

There have been motor racing heroes since four wheel competition began and Britain seems to have provided her fair share of these people. There is a strange mixture of factors in the creation of a motor racing hero, of course they have to be quick, that goes without saying, but there are other things that turn them into heroes. For Mike Hawthorn it was the devil-may-care attitude which everyone had come to love in the Spitfire pilots of World War Two which had ended barely a decade ago. Years later it was the appearance of being the perennial underdog which endeared even non-racing fans to Nigel Mansell (or ‘Britain’s Nigel Mansell’ as he was always known by the non-motorsport media). More recently we have seen Lewis Hamilton rise to cult status, looking hip and trendy with his hair braids and tattoos whilst at the same time behaving in exactly the way his sponsors and his public expect him to.

Roll all of these people into one and you have Stirling Moss. By the end of the 1950s, Moss was seen as a national hero. He epitomised the playboy racing driver as perceived at the time; wealthy, stylish and always with a pretty girl on his arm. He was fiercely patriotic, preferring to drive British cars whenever he could which immediately qualified him for the ‘underdog’ status. And he was the very first of the ‘professional’ racing drivers. He was very aware that this was his job and his living. In the commercial world of 21st Century motorsport he would be seen as a sponsor’s dream.

The accident...

All that changed on 23rd April 1962. Stirling Moss was seriously injured in the Glover Trophy, a non-championship Formula One race held at Goodwood on Easter Monday. He had started on pole position alongside Graham Hill’s BRM and Bruce McLaren’s Cooper (three abreast in those days). He made a strong start and was battling with Hill’s ‘stackpipe’ BRM when he called into the pits. Delayed enough to put him out of the race, Stirling nonetheless went back into the fray and set about catching the field. He put in the fastest lap at 1m 22s and was clearly entertaining the crowd. And then it all went wrong. Approaching the ultra-fast right hand part of St Mary’s, the Lotus 24 simply failed to make the turn and careered of at unabated speed into the unyielding earth bank.

The spaceframe car simply folded up around Moss, causing dreadful injuries to his legs, but the most worrying damage was to his head. Crash helmets were a million miles from the high-tech headwear of today. Herbert Johnson and Company had built a successful business providing cork helmets to the horse racing fraternity and these hats were de rigeur for motorsport world as well. Whilst these were undoubtedly a huge improvement over the previous linen helmets, in the case of a significant impact, they left the wearer extremely vulnerable.

Moss’s face cannoned into the steering wheel (no seat belts either, of course) causing significant injury. The tube frame of the Lotus had folded up at the front in the impact leaving the unconscious driver trapped. Bolt cutters were the first piece of emergency equipment needed simply to cut him free. After over half an hour in the wrecked car, he was taken to the Royal Sussex Hospital in nearby Chichester but his injuries were so severe he was transferred to the neurological unit at Atkinson Morley Hospital soon after.

He did not regain consciousness for 38 days.

The newspapers had been full of details, and some pretty graphic photographs, when the accident happened. Now the nation waited with bated breath. Hospital updates were front page news, but still the news was that Stirling Moss was in a coma. Over the next five weeks people started to wonder whether we would ever see Britain’s favourite racing driver again but eventually the news was better; he was sitting up and taking notice. He did not immediately realise that he was effectively paralysed and his physical rehabilitation was severely hampered by the fact that he could not move the left side of his body.

Stirling Moss said that he assumed it was his physical injuries which meant that he could not move, whereas in actual fact, it was the (thankfully temporary) damage to his brain which was the cause.

The recovery was slow, painful and difficult but eventually Stirling could walk again; more newspaper headlines, and eventually was released from hospital for a challenging recuperation. The world breathed again – Stirling Moss had survived!

The following year he drove a Lotus sports racing car at Goodwood in a private test session to see if he still ‘had it’. He decide that the spark wasn’t there, though years later he said that he still questioned whether his decision not to race again at the highest level had been too hasty.

The huge unanswered question is ’what went wrong?’

There was much speculation at the time, and intermittently ever since, about the cause of the accident. Moss has no recollection of the race whatsoever but some grainy cine film exists which shows the car spearing off the circuit at top speed. There seems to be no effort from the driver to make the corner and there is no indication that he lost control. The car simply didn’t make the turn.

There have been many guesses as to what happened, mostly without corroboration, but in 2012 the designer Len Terry (who created Formula One cars for Lotus, Eagle and BRM) wrote to Motor Sport magazine saying how he had lived with the knowledge that he might have been able to prevent the accident had he spoken up at the time. He had visited the workshop where the car was having its existing four cylinder power replaced by a new V8 engine. Terry talked about his unease about the quality of the engineering in the conversion, although obviously after 50-years the opportunity to seek out evidence was long gone. His discomfort at not having said anything at the time had stayed with him though, and he died two years later.

Stirling Moss has been an ambassador for our sport both before and after his accident. He continued to be a star for the fans and for the general public until his retirement from public life in 2017.

To many of us, me included, he is, and always will be, a hero.