Feature Story: Peter Lindner - Unsung Jaguar Hero

- 27 Jun 2018

The Lightweight E type story cannot be told without reference to Jaguar’s German importer, Peter Lindner. It was his Lightweight that the Brown’s Lane competition department rebuilt as the famous low drag coupe of 1964 for what turned out to be the XK’s last hurrah after fifteen years in the big European sports cars races and at le Mans.

Effectively, Jaguar’s competition department had withdrawn from competition at the end of the 1956 season, a decision compounded by the Brown’s Lane fire in February 1957 which destroyed much of the D type production line. However, the spirit of competition was in Jaguar’s blood. Privately owned D types continued to win races until about 1960 and by then and with tacit factory support, privateers were campaigning the Mark 1 3.4 in saloon car races to great effect. With the launch of the E type in March 1961, the temptation of closer involvement was becoming irresistible at Jaguar.

When a month later Graham Hill won at Oulton Park in John Coombs’s virtually standard E type and results notched up by the E types of Tommy Sopwith and Peter Berry were similarly encouraging, it became clear that Jaguar could not ignore the publicity opportunity a competition E Type could offer. So when the FIA announced that for 1962, the World Sports Car Championship would no longer be for sports prototypes, but for GTs with a minimum production of fifty cars, engineering director Bill Heynes authorised aerodynamicist Malcolm Sayer and chassis engineer Derrick White to develop just such a competition specification. Then the FIA changed its mind and opened the Championship to prototypes as well.

With no possibility now of an outright win, Jaguar abandoned the E type competition project. One aluminium panelled car, the so called Lightweight design, with a carefully flared roofline and flatter, lower windscreen, had been constructed and was eventually sold to Dick Protheroe and four lightened steel chassis, the basis for subsequent but unbuilt cars, were put into store.

However, pressure from privateers such as Guildford Jaguar distributor John Coombs or the American Briggs Cunningham who had faithfully campaigned Jaguars at le Mans for several years caused the competition department to revise its decision and resurrect the idea. A dozen or so special lightweight Es would be built for “carefully selected customers.” As well as Cunningham and Coombs, these included CT Atkins for whom Roy Salvadori drove, Bob Jane who took his E type back to race in Australia and Jaguar’s German importer, Peter Lindner.

None of these privateers, not even Briggs Cunningham, had done as much to promote Jaguar as Lindner who single-handedly had put Jaguar on the map in Germany, making it the Coventry firm’s third market. Peter Lindner was a classic product of Germany’s Wirtschaftwunder - the economic miracle of the 1950s which restored Germany after the rout of the war. At that time a remarkable optimism prevailed that things could only get better and it brought to the fore entrepreneurs like Peter Lindner. In 1952, aged only 22 he was a car salesman for a Wiesbaden auto dealer. One day he sold his first Jaguar and discovered that here was a car he liked almost as much as he liked selling them. He determined to run his own business and by 1955 he had enough funds to become an independent Jaguar dealer. Today, his nephew Thomas Fritz Lindner takes up the story:

“Obviously he wasn’t the only Jaguar enthusiast buying cars from Britain. There were several quite well known and established importers ranging from Neumann in Berlin to Autohaus Speck down in Freiburg who brought cars in from the Swiss importer Emil Frey; there was Fendler & Lüdemann in Hamburg or Birkelbach & Unkrüer in Düsseldorf. There was even Major Ronald Myhill of Overseas Motor Sales GmbH in Frankfurt. But they only sold tiny quantities. In 1954 for instance, they imported 21 cars between them.”

Lindner was ambitious: he could see that with the most developed road network in Europe and a taste for powerful cars, Germany could absorb many times more Jaguars than these amateurs were managing. Already quite well known at Coventry, he took the bull by the horns in 1957 and went straight to Sir William Lyons. The youthful German was not only charming and enthusiastic, he was convincing and, as Thomas Fritz puts it, “he was too young to be a nazi!” The deal was sealed with a handshake and Lindner returned to Wiesbaden as official Jaguar importer for the Bundesrepublik Deutschland.

Most of the early sales went to British or American servicemen stationed in Germany, but thanks to his boundless energy and imagination, Lindner began to wean sufficient Germans away from their Mercedes and other home grown marques. An enthusiastic driver, he would think nothing of rushing to an airport to close a sale or meeting clients at weekends and he campaigned his 3.4 Mark 1 (in British racing green of course) regularly on the circuits.

A combination of his somewhat bombastic driving style and the 190bhp of the XK sufficed to gain him plenty of victories: “He exemplified the ‘race on Sunday sell on Monday’ principle,” recalls Michael Riedner, auto historian, who goes on: “Under Lindner, Jaguar went from being an exotic wallflower to being a respected luxury brand in Germany.”

He also imported Aston Martins, racing his DB4 GT, and Lotus including the Lotus Cortina and raced that too, but Jaguar was his main activity and by 1964, his efforts had built up a network of 65 dealers. One of them was Roger Schweickert of Pforzheim: “I got to know him in the early 1960s when my father started buying Jaguars from him. Peter was a super fellow, open, warm, a good businessman.”

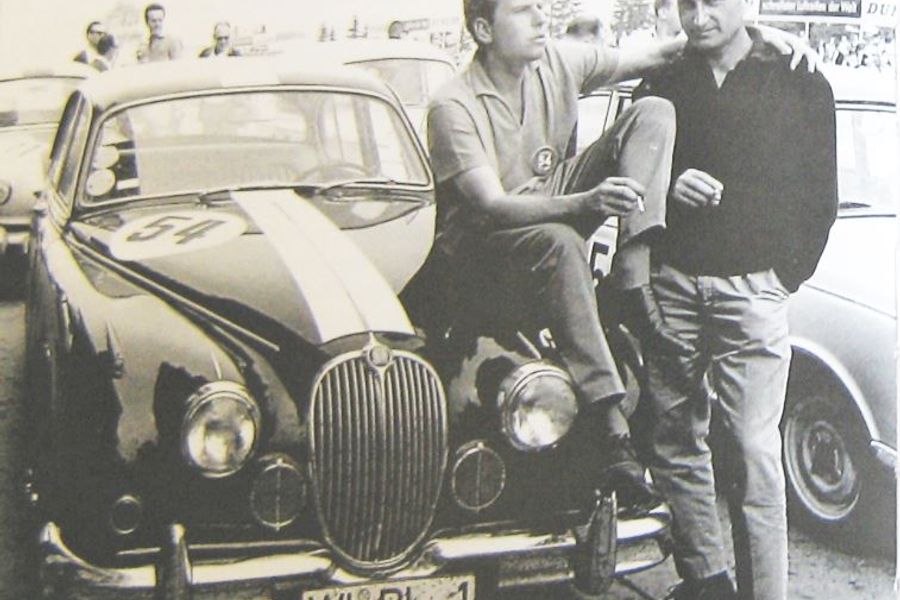

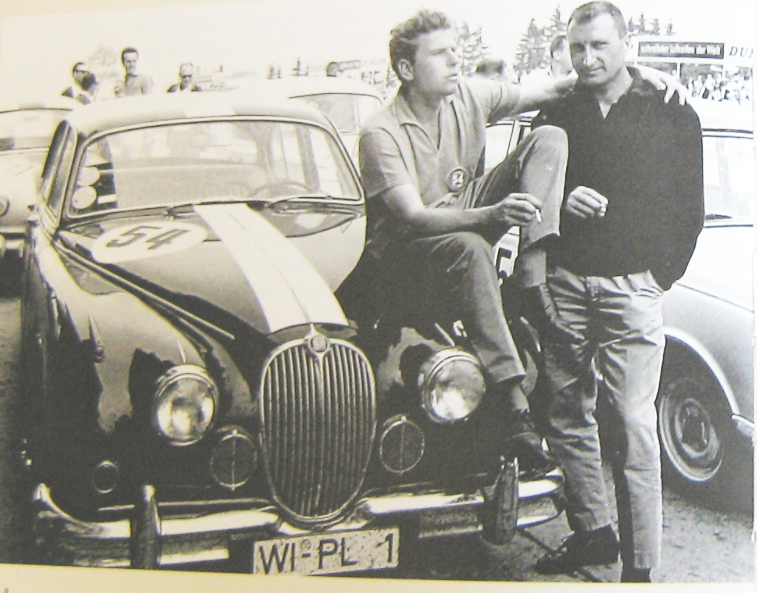

Roger Schweickert remembers a Peter Lindner who was good looking and always well turned out, a man who lived for business. “And he was a phenomenal driver! It was terrible when he was killed.” No mean racer himself, Schweickert’s father purchased Lindner’s works prepared Mark 2 3.8, though whether this really is Lindner’s famous WI-PL 1 and not one of the other factory 3.8s is disputed in some quarters. In any case the younger Schweickert recorded over 150 wins with it, finally retiring the 3.8 in 1999. Today, the most iconic racing Jag saloon outside Britain has a place of honour in Roger Schweickert’s showroom in memory of a man he obviously admired.

Indeed, Lindner’s personality was central to his business success. Confident and with a distinctly (and probably consciously) James Dean coiffure, he attracted celebrity types to Jaguar such as Hans Joachim Kulenkampf, for decades respected and best known anchor man on German television; he made a Jaguar owner of the actor Klaus Kinski. One day the unpredictable Kinski turned up at the Wiesbaden garage to have his car serviced: “He came with a girlfriend: neither of them had any clothes on!” smiles Thomas Fritz. “It was probably the only time my uncle was ever lost for words. But he quickly recovered and sent the workshop guys out for an extended lunch break!”

In business, Lindner was never knowingly undersold: Thomas Fritz produces Jaguar’s German pricelist for the 1961 Frankfurt show where the E type was the star and points to where Lindner has written over its price by adding a thousand deutschmarks. The advent of the E type helped to raise Jaguar sales in Germany by 50%, reaching 3000 units by 1963. Underpinning much of this success was racing: by 1961, Lindner had a works prepared Mark 2 3.8, registered WI-PL 1, and he won the German touring car championship.

This became a three car team the following year and Lindner recruited other drivers. The XK engine in the saloon was extremely reliable and looked after by Lindner’s faithful workshop boss, Hermann Simon, the 3.8, produced around 240bhp and never suffered a serious mechanical failure in its four track seasons with Team Lindner.

Lindner also hired Düsseldorfer Peter Nöcker as his co-driver for the longer events which really were the prestige races in the fifties and sixties. The relationship, at times a rivalry, but always a friendship between Lindner and Nöcker is interesting.

A couple of years older, the self effacing Nöcker was never in awe of Lindner. From a moneyed background, his family made its money from wholesaling building materials Nöcker was racing a second hand Mercedes 300SL by 1957. In 1962 he graduated to a Ferrari 250GTO. It was after seeing Nöcker race this car at the Nürburgring that Lindner invited him to join his Jaguar team. Initially sceptical, Nöcker adapted quickly to the Mark 2 and was 1963 European Touring car champion in that contest’s inaugural year, probably the Mark 2’s last major victory.

An accomplisher amateur himself, Peter Nöcker was no great admirer of Lindner’s driving skills and the Düsseldorfer was both the more consistent and usually quicker. Before he died in October 2007, Nöcker used to say that his former colleague’s first lap of a new circuit was usually as fast as his last; that he never improved. Certainly Nöcker was the smoother and when the pair acquired the fifth Lightweight E to emerge from Brown’s Lane, it was the older man who drove it to its victories at Avus and Innsbruck, but the two Peters, quite opposite in personality, were the original “dream team.”

Phenomenal driver Peter Lindner was not: he could be effective on circuits he knew well, but his style was often ragged and he lacked technical sympathy. Nöcker, who was consistently 15 seconds a lap quicker at the ’Ring complained that if anybody was going to break the gearbox, Peter Lindner would: “I raced for pleasure: for Peter it was a business, a means to an end.” After the victory, it would be the charismatic Lindner who hosted the press conference: his partner would quietly leave him to it.

In his absorbing book, Cat out of the Bag, former Jaguar apprentice Peter Wilson chronicles the development of the Lightweight E type and he observes with some feeling that Jaguar could have achieved much more with the discipline of a properly managed works team. At le Mans in 1964 for example, Lindner insisted on a roof scoop to provide better cabin ventilation.

As Peter Wilson points out, this effectively negated Sayer’s aerodynamic efforts with the roof and a works team boss would have overruled the driver or found another solution. But Lindner was a paying customer, not an employee. Like virtually all British racing teams after the war, with the possible exception of Vanwall, the Jaguar effort was under funded. Racing through third parties who in the case of the Lightweights, all purchased their cars from Jaguar (for the E type list price plus £1500 for competition preparation) was the only option.

For the 1964 season, the competition department had thrown its support behind Coombs for British competition and Lindner for the continent and le Mans. To this end, Brown’s Lane rebodied the German car with Sayer’s fared nose and the Low drag roof, designed for the aborted ’62 GT championship. The intention was to increase the Jaguar’s top speed especially for the three mile Mulsanne straight. A new, if heavy ZF speed gearbox endowed a fifth ratio and the XK engine was subject to porting work giving it 322bhp, the highest output yet. A le Mans practice time of 4:05.9 flattered only to deceive though as in the race itself the Lightweight retired with irredeemable loss of coolant when in 12th position.

Its next outing at Zolder ended in another retirement and at Goodwood for the Tourist Trophy, neither driver could get to grips with the circuit. Peter Wilson speculates how much more successful the whole venture might have been if Lindner had hired a top flight professional driver. Earlier in the season, Graham Hill had lapped Goodwood in 1:26.8 in the identically set up Coombs Lightweight, yet neither Lindner nor Nöcker could get within eight seconds of this on the 2.4 mile Sussex track. As it was the car collided with the bank at Woodcote and was a non starter.

The next engagement was the Paris 1000km at Montlhéry and in a season without even a finish, Lindner who was losing interest, had decided to sell the E type before 1965. Roger Schweickert claims that in September 1964 Lindner was negotiating a million mark loan to develop his car business (c£90,000) and that one of the bank’s conditions was that he gave up racing. Whatever the financial background, the XK was now delivering 344bhp its greatest output yet, but seemingly was still not reliable, nor in the face of V8 rivals like the AC Cobra or Ford GT40, competitive.

A further sad irony of the Montlhéry race was that at two thirds distance, the XK was running well in sixth and as close to finishing a race as it had been all year. Lindner’s inexplicable accident (though one theory is that a wheel broke) in front of the pits killed five people including the wretched Wiesbadner who characteristically was not wearing the factory seat belt and was thrown from the E type as it rolled over and destroyed itself.

At his boss’s side to the end, Hermann Simon was one of the first on the scene. He said at the inquest that Lindner was still able to speak though evidently in great pain. He managed to tell Simon to get everything packed up and back to Frankfurt then he lost consciousness and never regained it.

It was the last word in a chapter already closing fast, for 1964 marked the eclipse of the 3.8 saloon, in Britain by the V8 powered Ford Galaxie and at the Nürburgring by the Mercedes 300SEL. The Paris 1000kms was the last ever outing by a competition department prepared XK.

It was the beginning of the end of Auto Salon Lindner too. Jaguar was prepared to stand by Peter’s widow through the unpleasantness of insurance claims and counter claims (which, Peter Wilson says, dragged on into the 1970s), but without the personality and energy of Lindner himself, the heart had gone from the enterprise. A new firm, Düsseldorf based Brüggemann, eventually took over, but Peter Lindner’s was a hard act to follow.

Two of his mechanics, Hellmuth Schöne and Hans Dieter Lemke later established their own Jaguar business in nearby Frankfurt. Like Roger Schweickert, they have fond memories of their flamboyant boss. On the Lemke & Schöne website, the founders describe themselves as former Lindner technicians very much as if this were a badge of honour. Hellmuth Schöne, who is now retired is still keen to talk about Peter Lindner: “He really was a very nice man. I had come from East Germany and after that Auto Salon Lindner was an absolutely wonderful place, great atmosphere to work in.”

Herr Schöne also confirms that Peter Nöcker was the better racing driver; he describes how Lindner though would drive them back to Wiesbaden after a race at the ’Ring as if he were still competing, downright hair raising, but very exciting. “Er war draufgängerisch!” which translates as pushing, daring, adventurous. And he lived life to the full: “Immer vollgas!” (always foot to the floor) adds Dieter Lemke of a Lindner famous for covering the 30km door to door between his Wiesbaden and Frankfurt premises in 10 minutes….

These comments sum up Peter Lindner. Personable but bold in his dealings with others, audacious on the track as in life, a better businessman than a racing driver and tireless in both roles, he established Jaguar on the continent in the post war world. And like all too many pioneers, he took risks of which one proved to be particularly ill judged.

Kieron Fennelly

Popular Articles

-

December Podcast: Derek Warwick Part Two...F1, Le Mans and More!9 Dec 2024 / Podcast

December Podcast: Derek Warwick Part Two...F1, Le Mans and More!9 Dec 2024 / Podcast -

November Podcast: Warwick, Whitaker, Evans and the usual Wittering16 Nov 2024 / Podcast

November Podcast: Warwick, Whitaker, Evans and the usual Wittering16 Nov 2024 / Podcast -

October Podcast: Featuring Sir Jackie Stewart!10 Oct 2024 / Podcast

October Podcast: Featuring Sir Jackie Stewart!10 Oct 2024 / Podcast -

October Emergency Pod!: The Two Pauls Talk British Circuits3 Oct 2024 / Podcast

October Emergency Pod!: The Two Pauls Talk British Circuits3 Oct 2024 / Podcast