Many thanks to our colleagues at DailySportscar.com for allowing us to bring you this lavishly illustrated review of a new mighty tome on the race activities of long-time Porsche supporters the Kremer Brothers, written by Porsche expert Michael Cotton, Ulrich Trispel and Robert Weber:

The Kremer brothers, Erwin and Manfred, built, prepared and raced Porsches that won most of the top prizes in endurance racing over a period lasting nearly four decades.

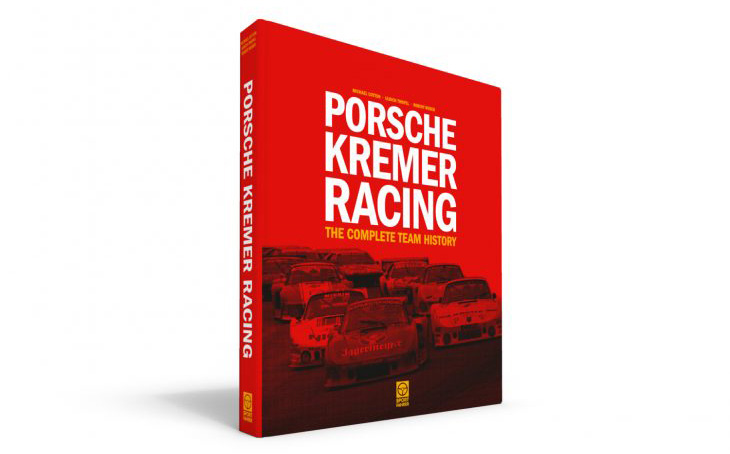

The story of this magnificent team is told in a book titled Porsche Kremer Racing, published by Robert Weber’s German company Sport Fahrer. It’s a big book, heavy, fully illustrated, a complete history of one of the most successful private Porsche teams in history.

The Kremers began small, in 1962, building up a Porsche 356 they found in a scrapyard, operating out of a small workshop in Cologne.

It was hand-to-mouth for years but they graduated to the 911, Erwin racing when he had some money, Manfred preferring to keep safe behind the pit wall organising the team.

The breakthrough came in 1968 when Erwin, teamed with Willi Kauhsen and Helmut Kelleners won the Spa 24-hours in his tuned up 911L, homologated as a touring car, powered by a 210 horsepower Carrera 6 engine. Auto Kremer was in business, Kelleners winning five events in the European Touring Car Championship (which included the Eigental Hillclimb in Switzerland), though narrowly pipped to the title by Dieter Quester in a works BMW 2002.

By 1970 Porsche Kremer was a flourishing company, and Kremer Racing was becoming one of the most successful privateer teams in motorsport history. The big result that year was a magnificent class win at Le Mans, the rain-drenched event that provided Porsche with their first outright victory, with Kremer’s 911S finishing in seventh place overall, of 12 finishers, entered by Ecurie Luxembourg and driven by Erwin Kremer and Nick Koob.

If anyone didn’t yet recognise the name of Porsche Kremer, they did now. Kremer drivers won the prestigious Porsche Cup no fewer than 11 times between 1971, with John Fitzpatrick, and 1990 with Bernd Schneider. Fitz won the Cup three times, Bob Wollek four times, and a Kremer driver won the European Grand Touring title three times in succession 1990-1992.

By 1973 Auto Kremer had an annual turnover of a million D-Marks, selling perhaps 20 new Porsches a year, more pre-owned, always specialising in tuning and race preparation. On the track, Kremer Racing’s battles with Georg Loos, from the other side of Cologne, became legendary, the property dealer spending whatever it took to win races. Honours were fairly evenly shared in 1974-75, with Fitz swinging between the Kremer team, which he favoured, and the Loos team which outbid for his services. In the end, Fitz won the ’74 title with the Kremers having driven for both teams, so the bragging rights remained with the brothers.

The Kremer programme was stepped up in 1976 with the introduction of the Porsche 935 Group 5 machine with its turbocharged engine. Jochen Mass and Jacky Ickx led the factory’s Martini sponsored team, but the factory was astonished when the Kremers turned up for the opening round of the new World Championship for Manufacturers with a 935 that looked very much like the works car!

A friend had taken sneak pictures of the works car testing at Le Castellet, the bodywork had been mostly replicated, and Bob Wollek and Hans Heyer were booked to drive the 935K1. Yes, the first time the K suffix had been employed. It was not as fast as the works car, losing two seconds per lap, but it was quicker than the Schnitzer BMW CSLs by three seconds per lap. After six hours the Kremer Porsche, completely unsponsored, finished in second place six laps adrift.

The Kremer 935K1 remained in contention through the 1976 season, lost victory at Silverstone by having its turbocharger replaced in 17 minutes, but claiming second place to the Hermetite BMW driven by John Fitzpatrick and Tom Walkinshaw. BMW took advantage of a bout of Porsche unreliability to vie with Porsche for the title, and with two final victories, the Martini team clinched it by 10 points, the 15 earned by Kremer at Silverstone tipping the balance.

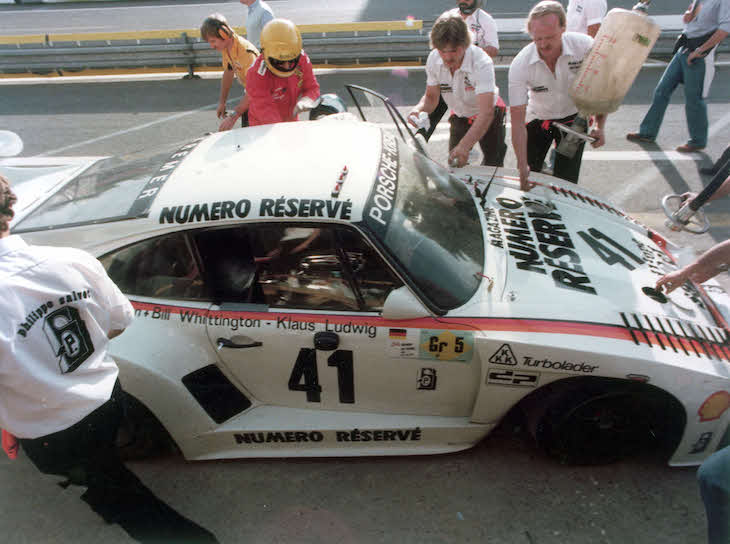

Kremer Porsche fought fiercely in the next two seasons, but their programme peaked at Le Mans in 1979 when their 935K3 became the outright winner of the 24-Hours, the first production-based car to do so, arguably, for 25 years. Klaus Ludwig was the winner, and he was partnered by the American brother’s Don and Bill Whittington, who bought the car on race morning in order to claim the start for Bill. “How much?” they asked, and told the price, took a suitcase to Manfred crammed with $290,000 in notes. It was drug money, but that was proved much later.

With unreliability afflicting the factory Porsches and the Cosworth powered Mirages, the contest to the chequered flag went in favour of the Jagermeister sponsored 935K3 ahead of the Dick Barbour 935 raced by Rolf Stommelen with Paul Newman with Barbour. Icing the cake, Kremer’s second 935 claimed third place overall in the hands of Laurent Ferrier, Francois Servanin and Francois Trisconi.

Barbour bought a K3 for the 1980 season and he and Fitzpatrick won the Sebring 12-hours outright (Fitz drove for nine hours). Fitz went on to win seven of IMSA’s 14 rounds to seal the title.

The 935K4 was built 1981, the most formidable Group 5 car ever raced. It was based on a tube frame chassis similar to that of the Porsche 936 and won the German DRM championship for Bob Wollek, who also collected the Porsche Cup for the fourth time, in 1981.

Barbour ran short of funds and Fitz launched his own race team in 1981, purchasing the same K4 while describing it as “a sensational car, the fastest 935 ever”. He and David Hobbs raced to fourth overall at Le Mans, winning the IMSA GTX class, and he scored three wins in the States to finish third in the IMSA series.

Time to move on, for the Kremers. Lacking a competitive car for Le Mans in 1981 they took an outrageous step and built a brand-new Porsche 917 which they dubbed K81, driven by Bob Wollek and sponsored by Mallardeau Residences. The frame was made of heavier aluminium tubes, to cope with the higher cornering forces obtained with modern race tyres. It, unfortunately, lacked top speed on the Mulsanne, and Wollek worked hard from midfield to reach 12th place at the end of his stint. Guy Chasseuil got the 917 up to ninth, good going on Saturday evening, but Xavier Lapeyre spoiled the show by running out and damaging an oil line, which led to retirement.

The Kremers had another new-build for 1982, building a Porsche 936 to factory specification, officially chassis 05 (below), which Rolf Stommelen drove in the DRM series, reaching the podium in each of his five starts.

Nor was that all. The brothers also built their own Group C car, the CK5, which they described as “a mix of 908/03 and 936 tube frames with a roof on top”. Don Whittington, Ted Field and Danny Ongais sponsored the car for an all-American debut at Le Mans, where they declared themselves “thrilled” with the handling, though it retired after two hours with a failed engine.

The CK5 was then assigned to Rolf Stommelen for some DRM events, including a win at Hockenheim, and a DNF with a failed starter motor at the World Championship race at Spa, where he was joined by young Stefan Bellof.

All this was marking time until the Kremers took delivery of their first ground effect 956, chassis 101, for the 1983 season. Australians Alan Jones and Vern Schuppan got the season off to a good start with a fifth place at Silverstone, and then, with Kenwood sponsorship, Mario and Michael Andretti, with Philippe Alliot, raced to third overall behind the Rothmans Porsches. The good times were back again! But the competition was getting stronger, as more teams got to grips with their new Group C cars, and the only outright win of the season was in a non-championship race at Diepholz, where Franz Konrad took the flag.

Let’s skip a year to 1985 when Kremer Porsche scored their first outright victory in a Group C World Championship race, with their new 962C in the Monza 1,000 Kms. Manfred Winkelhock and Marc Surer were the successful drivers in the race shortened by what the French would call a force majeure when strong winds felled a tree across the track at the Lesmos. Most teams had recently refuelled, were coming past the pits with foliage fluttering on the wipers and bodywork, then the flag came out… and Winkelhock was the first over the line! He was due in the next lap, good fortune for the Kremers.

Later in 1985, they suffered the most grievous loss as Winkelhock died as the result of an accident at Mosport, possibly resulting from a loss of tyre pressure. “The worst thing is when you lose someone,” remarked Manfred, and it was effectively the end of their season.

They signed Jo Gartner for the 1985 season, and the young Austrian promptly won the Interserie race at Thruxton, following up with a second-place, to Hans Stuck, at the Nürburgring. Eighth at Monza, third at Silverstone, the good times were back again, but not for long. Gartner tragically lost his life at Le Mans, his Porsche going out of control on the Mulsanne Straight for no clear reason, and the brothers were grief-stricken.

Later, the Kremers had honeycomb aluminium chassis made by John Thompson in England, and then a new chassis constructed of carbon-fibre.

The last Kremer sports cars were the K7, built in 1992, and the K8 which made its debut at Le Mans in 1994, and won the Daytona 24-Hours in 1995. With the iconic Gulf Oil livery, Derek Bell, Jürgen Lässig and Robin Donovan dove to an untroubled fifth place at Le Mans in 1994, and half a year later the K8 was triumphant at Daytona in the hands of Lässig, Giovanni Lavaggi, Christophe Bouchut and Marco Werner, making his debut with the team as a reserve driver, and impressing.

The Kremer story went on and on. They bought a GT1 from the factory for the 1997 season, it was not a success, either for the factory or its customers and reverted to the K8 for 1998, then switched altogether to a Roush Ford powered Lola B98 for the next three seasons. It just wasn’t the same.

Erwin died in 2006, Manfred retired to Spain, but later bought the Kremer assets. The team was reformed under new management in 2011 to campaign Porsche GT3 Cup cars and market their K3- retro styling kit, racing primarily at the Nürburgring until it folded quietly in 2018. It was a hell of an era!

‘Porsche Kremer Racing’ can be ordered from www.sportfahrer-zentrale.com for 95 Euros, plus postage and packing. It has 390 art-work pages, is fully illustrated, and weighs 3 kg.

Pictures Copyright Porsche, Sportfahrer and John Brooks